The Interpretivist Lens – What Design Study as a Method of Inquiry Can Teach Us.

Much of the current conducting and reporting on design studies leaves little room for contributions outside of the end tool or technique. An interpretivist approach embraces the messy, subjective nature of design studies and emphasizes the ways in which we can conduct research of this nature with rigor. In this post, we advocate for interpretivist design studies and give three recommendations for conducting them.

Research in our lab is often conducted through design studies; applied visualization research to address real-world problems. In recent work, we experimented with methods to conduct design studies from an interpretivist perspective. In this blog post, we advocate for interpretivist design studies and give recommendations for conducting design studies through an interpretivist lens. This perspective can lead to more diverse contributions, more rigor, and learning opportunities.

But first – what is an interpretivist design study? What do we mean by interpretivist? Much of the established methods for conducting scientific research is grounded in a positivist approach to inquiry, where there is a single reality that can be understood by observation. Interpretivism stands in contrast to positivism and holds that reality is subjective, socially constructed, and a composite of multiple perspectives. Through this lens, research is inherently shaped by the researcher, who brings their own subjective view of observed phenomena based on their personal experience. Generated knowledge is not an absolute truth, but relative to the time, context, and culture that it emerged from.

Which side are we (visualization researchers) on?

Visualization research benefits from both positivist and interpretivist perspectives, though the latter gets little consideration in design study reporting. This is a shortcoming, as a core aspect of applied visualization research is understanding people and their (data) problems. We rely on the perspectives of our domain analysts to understand the problem space. A space that is constantly shifting as we learn more about the domain. The process of visualization tool development is subjective and indeterminate, resulting in a solution that is not objectively right or wrong.

Design studies are typically evaluated by the resulting tool or technical contribution, and reviewers tend to ask for generalizable contributions. There is little focus or scrutiny on the messy, subjective process that leads to the tool. A process that is filled with a multitude of valuable insights that never see the light of day under the traditional structure of reporting on design studies.

An interpretivist approach emphasizes rigor in the methodology used. In recent work, Meyer and Dykes defined criteria for rigor in applied visualization research. We focused on three of these criteria (REFLEXIVE, ABUNDANT, TRANSPARENT) in our most recent design study with evolutionary biologists. By focusing on these criteria, we were able to engage with the design study in new ways resulting in two technical contributions, two experimental writing techniques, and three methodological insights.

We pose these questions to the greater community – what could an interpretivist perspective do for your work? What insights could it afford? Could it establish a more rigorous outcome? And we present some guidelines for how to conduct and interpretivist design study.

Recommendations for conducting an interpretivist design study:

So you want to conduct a design study with an interpretivist lens? We have some recommendations for you to consider before you start.

1. Establish systematic reflective practices that include reflexive notes, reflective transcriptions, and artifact curation;

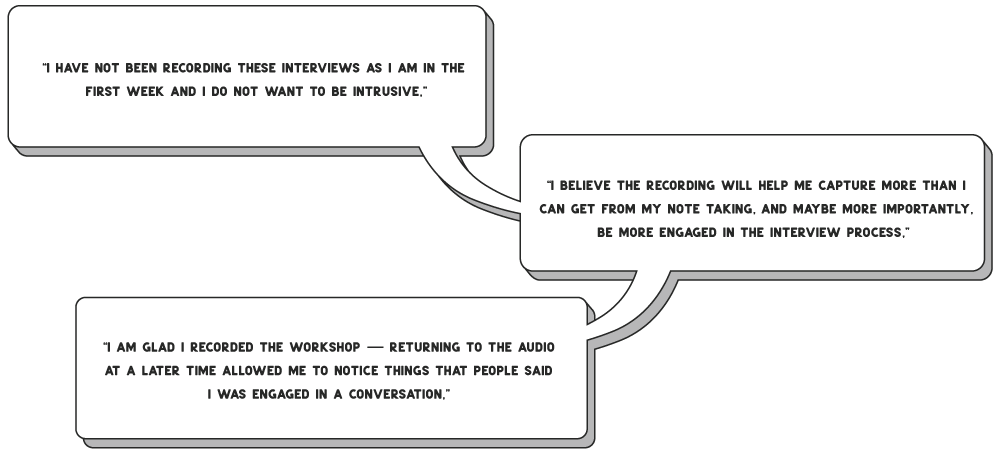

Regular reflection was a vital part of the study process. Much of the collected artifacts generated during our study were regular memos I took during meetings and observations during our field study. Regular reflective memos were reflexive in nature. Reflexivity is the explicit awareness of the researcher’s own role in their research. These memos allowed me to make insecurities that affected the research explicit. For example, I was not recording meetings during the first couple of weeks of the field study because I was nervous about being intrusive. I wrote this down and by externalizing these thoughts, and reflecting on my observations I adjusted my research practices. When I started to record, I was able to engage with interview participants better because I no longer needed to try to take speed notes as we were talking. The recordings became an important tool for reflection where I could revisit previous recordings and get more context for the notes I had taken. The act of organizing the collection of artifacts was also a great benefit to the design and development of the tool.

2. Build and maintain a trace of diverse research artifacts (and do it early);

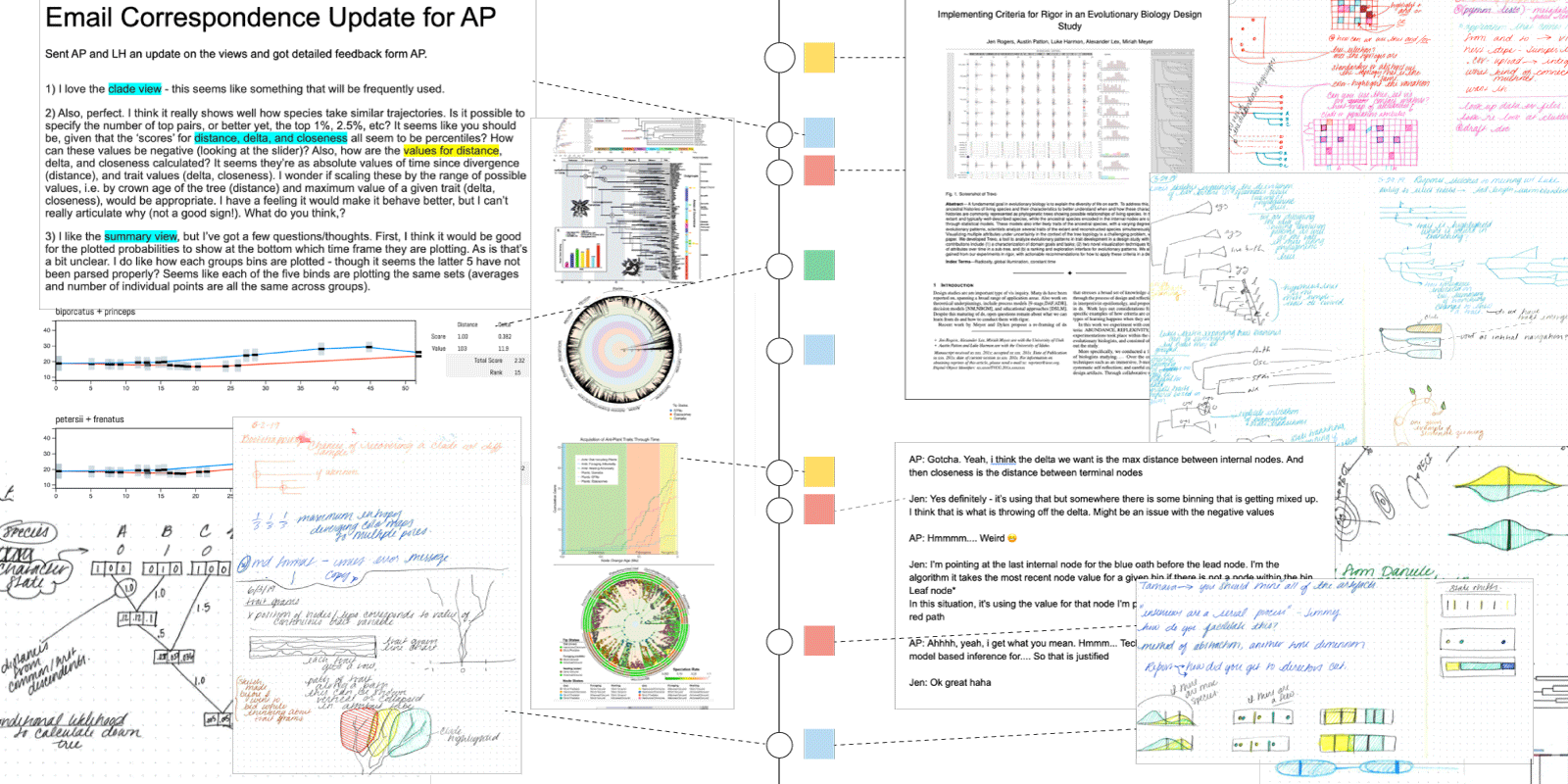

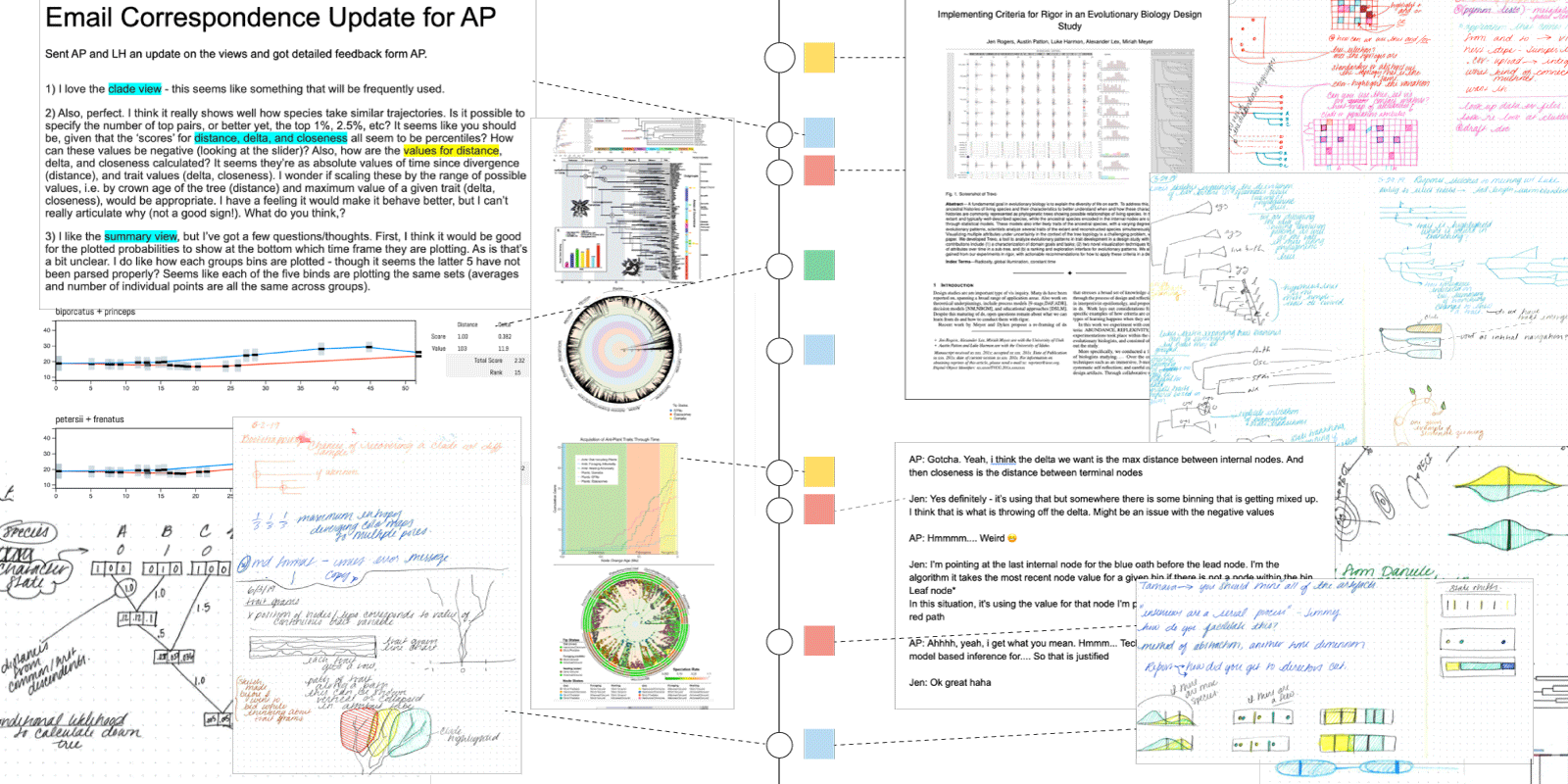

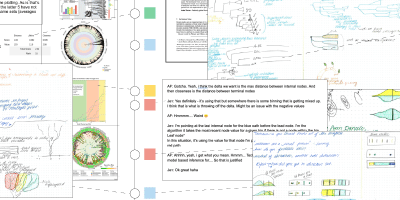

We attempted to collect an abundance of artifacts to transparently communicate the design study process and emergent insights. We gathered sketches, emails, memos on meetings and observations in the lab, whiteboard doodles, diagrams, paper drafts, data, and text messages. Our initial intention was to create an audit trail to transparently communicate our study, supplemental to our paper. As our collection grew, we realized that transparency relied on a system that would allow people to trace insight back through the study. We created a system for indexing and tagging the artifacts from the collection, using this as the backbone of a web-based audit trail. Organized in a timeline layout, this allowed for tracing the study temporally. When we built this audit trail we inherently reflected over the research artifacts, and our collection began to serve an unexpected use as an internal research tool. The tagging system we had created allowed us to trace insights by concept, as well as, temporally. This led to the concept of tRRRace, which supports Recording, Reflecting, and Reporting on a design study. A diverse set of artifacts supported the ability to trace emergent concepts and this was important for both reporting and reflection when it came to generalize and communicate the study results. We recommend that you record as much as you can. Collecting artifacts greatly benefited from a system of organization early in the process. Along with this, was developing a system for handling privacy. Both of these aspects get significantly more tedious the farther into the study you are.

3. Argue for rigor from evidence, not just methods.

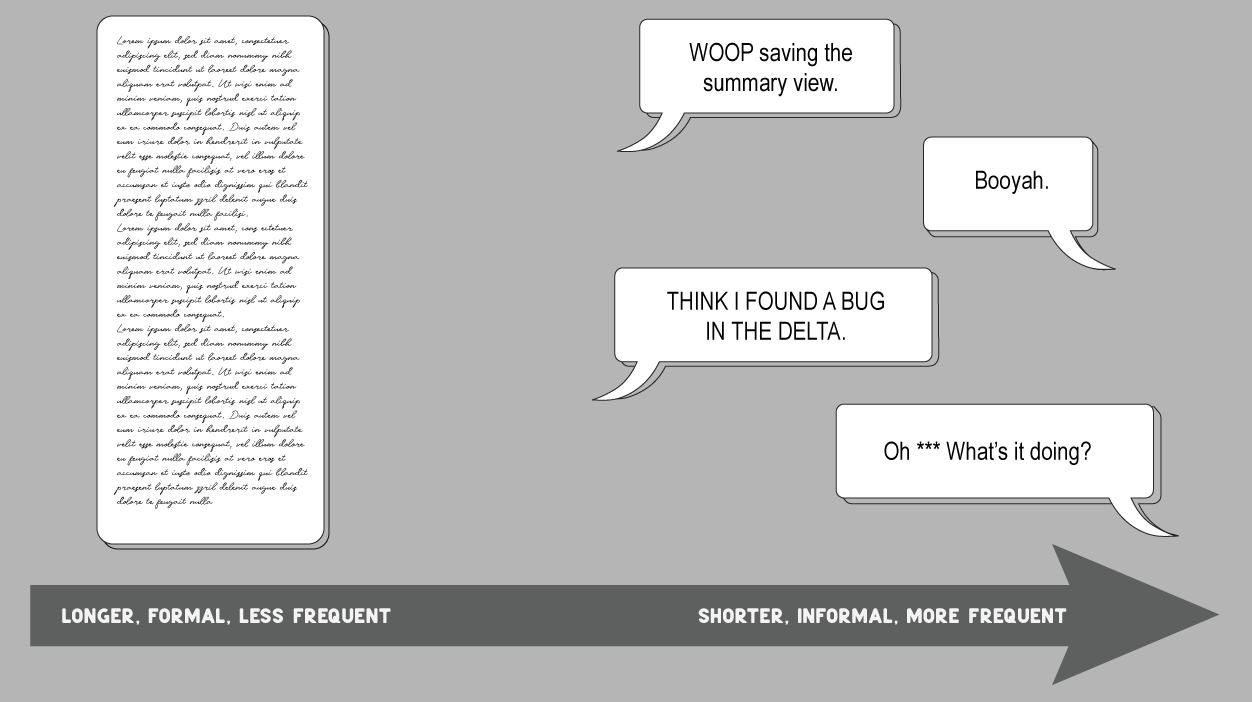

Justified research methods are necessary for achieving rigor in a design study. But these are not enough. Evaluating whether a study is rigorous relies on evidence in addition to justified research methods. For our study, we found evidence of one aspect of rigor when we reflected over the collection of artifacts from the change in frequency and tone in communication with our collaborators. In the beginning, much of our communication was in the form of semi-structured interviews. This was longer in duration, less frequent, and formal in tone. Reflecting over the memos we noticed that the communication shifted to more frequent, shorter, and less formal text messages and emails. We concluded that the evident changes in communication, not the time we spent in the field indicated our design study met aspects of the INFORMED and ABUNDANT criteria. Situating this evidence within existing theoretical concepts (for this, we looked at design by immersion), we could draw meaning from the observations we made in the study. We encourage resisting the urge to argue that a study is rigorous because of a checklist of methods used. Instead, we should be looking for evidence of things that changed, shifted, and surprised us.

Conclusion

An interpretivist perspective widens the focus of a design study’s knowledge contribution to include more space for insights separate from the end tool such as methodology, writing devices, and patterns in social dynamics. Along with this, it emphasizes the ways we can conduct such a subjective, messy research endeavor with rigor. Our experiments with rigor led to a wealth of learning opportunities. Much of these opportunities were intertwined and are difficult to distill, and these recommendations are just a starting point. This space is rich in learning opportunities in which our contributions have just scratched the surface. We hope this is the beginning of a continued conversation about what we could learn from design studies, and how we can communicate these diverse insights to our community.

The Paper

This blog post is based on the following paper:

Insights From Experiments With Rigor in an EvoBio Design Study

IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics (InfoVis), 2021