What we Should and Shouldn’t Change About the VIS Review Process

The review process at IEEE VIS hasn’t changed in the last decade. Here I lay out some suggestions to make the process more equitable, open, and to possibly raise the quality of reviews.

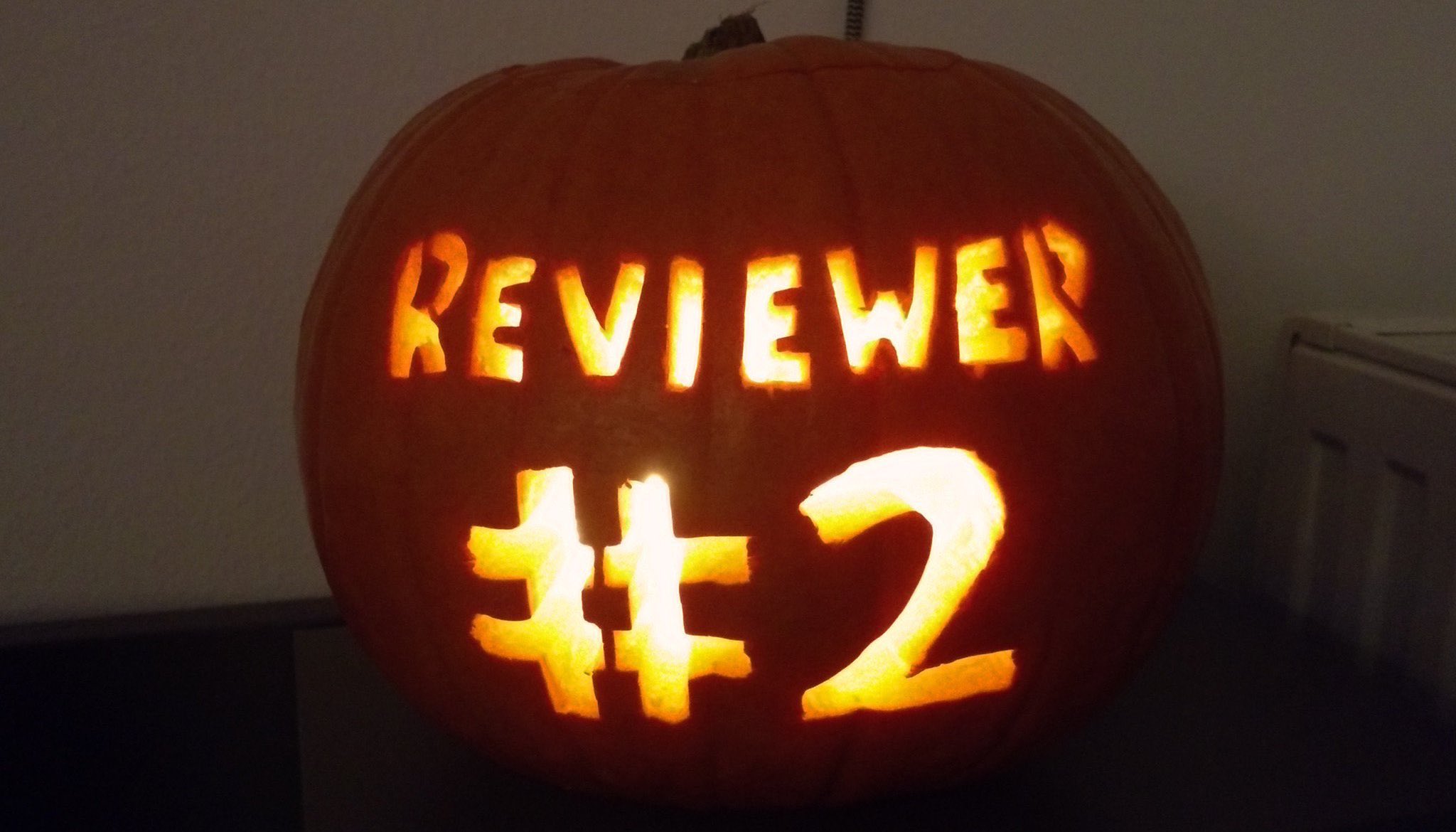

Image by Clara Nellist, used with permission.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how to structure VIS in my role as a member of the reVISe committee. Last week at VIS, the committee got a few questions regarding changes to the review process. reVISe explicitly did not tackle reviewing beyond what was necessary for the unification of the three conferences. One step after another.

I do have some personal opinions about the review process and what we should (not) change, which I wrote up here. Note that this does NOT reflect the reVISe committee’s opinion – we didn’t even discuss most of these issues.

So, here we go:

1. We should be doing double-blind reviews.

There is a lot of evidence that double-blind reviewing reduces bias, and it’s hence not surprising that double-blind or partially double-blind reviews have been implemented by the vast majority of CS conferences. VIS is currently optionally double or single-blind – the authors choose.

There are two main arguments in favor of single-blind reviewing: (1) it enables us to manage conflicts more easily, and (2) it is easier to implement open science practices, such as preprints.

Conflicts: We can declare conflicts with institutions and authors without seeing the papers, and systems such as PCS (the submission and review tool used by VIS) could be improved to automatically flag co-authors of prior submissions as conflicts and to carry over conflict declarations between years and conferences. This might result in some overlooked minor conflicts, which later may require some last-minute shuffling by the paper chairs. However, I’d argue that reducing the potential for bias is worth that additional administrative effort.

Open science/preprints: Double-blind reviewing is pointless when the authors post their submissions to a preprint server and promote it on Twitter right after submission. Preprint embargos (e.g., don’t submit your work to a preprint server between two weeks before and eight weeks after the submission) and social media embargos (don’t promote your preprint under review on Twitter) are reasonable allowances that are compatible with the desire to quickly disseminate most work. Paired with reviewer instructions to not explicitly search for paper titles or the like, I believe that this would be a reasonably good system, and let’s not let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

Another argument I sometimes hear is that “I’m able to tell authors identities anyways because only group X works on problem Y / system Z”. Sure, sometimes we might have hunches on where a paper is from. It’s likely that it’s from UW when it’s about an extension to Vega Lite, or it’s probably the The Birdbassador calling when Tarot cards are featured. But in my experience, I really only can guess the authors on very few occasions with any kind of certainty.

I also think we should avoid partial anonymity, which is the situation when a coordinating reviewer or program committee member – the primary and/or the secondary – know the identity of the authors. Primaries and secondaries have an outsized influence on a paper’s acceptance and hence it’s especially important to avoid that source of bias. The usual argument for why primaries and secondaries have to know the author’s identity is to avoid conflicts when assigning externals. I think that’s a flawed argument, since many conflicts aren’t obvious to an outsider, and a solution to this problem would again be technical: PCS could prohibit the assignment of external reviewers with known conflicts with a paper.

2. We should not have rolling deadlines

I’ve heard calls for rolling deadlines (e.g., three deadlines per year, as CSCW does), usually either with the argument to make sure authors submit the paper when they feel that it’s ready and don’t feel rushed to submit half-baked work, or as a call for improved work-life balance, as deadlines tend to be all-consuming in terms of the authors’ time commitment.

While I don’t feel as strongly about this as I do about double-blind reviewing, I think rolling deadlines are a bad idea for VIS.

Why?

First, we already have a completely deadline-free alternative as TVCG journal papers are invited to be presented at VIS.

Second, we have at least two other excellent venues for VIS work: EuroVis and CHI. While CHI may not fit all flavors of work presented at VIS, EuroVis definitely does, and these conferences have deadlines that are fairly spaced out over the year, so missing the March 31st VIS deadline isn’t such a big deal. Introducing a rolling deadline model might cannibalize these independent venues, especially EuroVis.

Third, to present at a conference in a particular year, there would still have to be a “last” deadline. I don’t have the data on this for CSCW (let me know if you do), but I suspect that will still be the most popular deadline.

On the flip side, rolling deadlines mean additional organizational overhead. And to be frank, I personally like how a deadline motivates me to work hard, clear my schedule to focus, and ignore all e-mail for a week or two.

3. We should not require signed reviews

In a signed review, a reviewer discloses their identity as part of their review. I’ve done at least one signed review, but I think we should not require signed reviews.

The reasons for this are fairly obvious: you don’t want reviewers to fear retribution if they review a paper of (what they suspect might be) a powerful author who could hire them, write their tenure letters, or invite them to serve on organizing committee roles. It’s just a lot easier to be frank if your career is not at stake.

The counter-argument is that you should only write a review that you stand behind publicly and that signed reviews ensure that your review is careful and fair. I would argue that these two things are at least partially already enforced given that the paper chairs and (other) PC members on a paper you review know your identity and will judge you and not invite you back if your review is bad or even abusive. Also, see my next point about publishing reviews on this matter.

And as an author, I personally prefer not knowing who my reviewers were, so I can have a beer and a chat with them at the next (in person) VIS party without holding a grudge.

I believe anonymity makes for a nicer community.

A related question is: should you allow signed reviews? I’m not sure about that. Mostly we would be protecting reviewers from themselves, but reviewers are grown-ups, so maybe it’s OK to let people disclose their identity if they want to.

4. We should publish revisions, reviews, and rebuttals with papers

I’ve had my share of experiences with dreaded Reviewer #2, like, I’m sure, everyone has. And while I don’t think we should force reviewers to reveal their identity (see above), I think we should publish revisions of papers, reviews, and rebuttals.

Currently, IEEE disallows publishing reviews you received on a paper. We tried to do that for our experiments with rigor paper but we were told that while IEEE is currently reviewing its policy on this, it is currently not allowed.

Public reviews will likely increase the quality of reviews without the negative aspects of signed reviews. Public initial versions of papers will likely lift the quality of the papers submitted. Finally, we should allow authors to publish reviews of rejected papers.

I don’t think we should disclose review scores – we don’t need to signal how “good” or “bad” a paper is with just a single number, but the hopefully nuanced discussion in a review should be part of the record.

Conclusion

There are a few other things we need to consider going forward: do we really need four reviews for every paper, or are three sufficient? How do we deal with content made available outside of the submission system, such as live demos or data repositories?

But I think addressing the things I discussed here are the most important and will make the IEEE VIS review process more equitable and overall fairer and better. As I mentioned before, I don’t feel equally strong about all of these points. Abolishing single-blind reviewing is certainly long overdue. Open reviews, on the other hand, are a fairly radical idea by VIS community standards. I think the quality of VIS would benefit from it, though.

If you have a comment, please start a discussion on Twitter.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Nils Gehlenborg for discussing these issues and disagreeing with me and to Derya Akbaba for comments and edits.