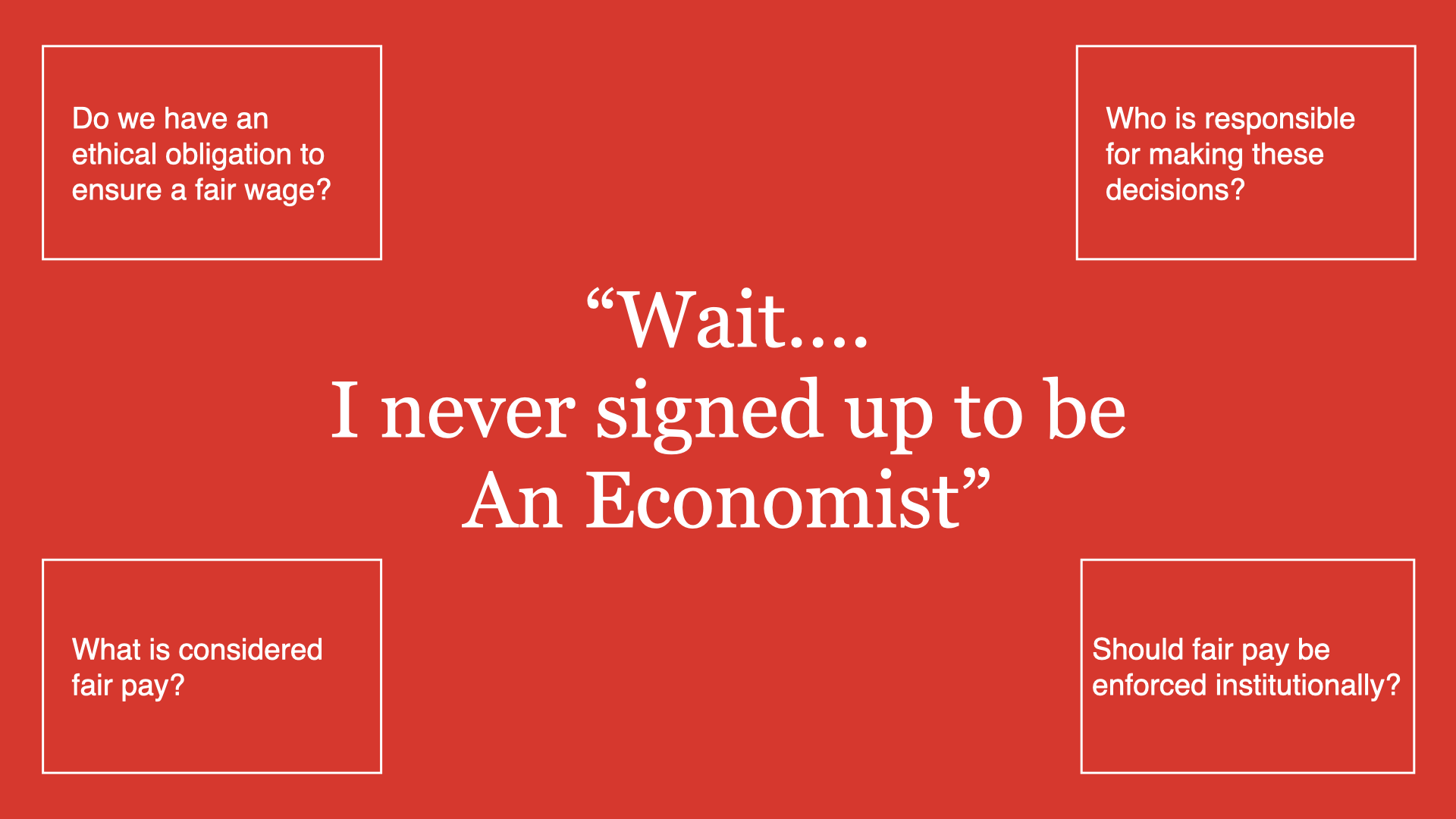

Wait... I never signed up to be an economist

Conducting user studies to evaluate visualizations is a popular approach for evaluation. During the pandemic such user studies have migrated to crowdsourced platforms due to restrictions on in-person studies. Do we pay the participants in our studies fairly? Is it our job to do so? Our panel at IEEE VIS 2021, explored the above questions and many more.

Kiran Gadhave and derya akbaba co-organized a panel at IEEE VIS 2021 titled “Wait…when did we sign up to be economists?” The panel was moderated by Carolina Nobre, and the panelists – Saiph Savage, Danielle Albers Szafir, Alexander Lex, Steve Haroz, Khairi Reda – were tasked with debating the ethics surrounding the decisions researchers make when determining the how much to pay crowdsourced study participants. The following article is a summary of the key points brought about by the panel. A recording of the panel is also available.

Although we don’t know exactly how many papers submitted to IEEE VIS over the years used study participants, from anecdotal experience, it’s a lot. And during the pandemic, due to restrictions on in-person activities, such studies have moved online to crowdsourced platforms. This becomes problematic when research has shown that most crowdsourced workers make way less than minimum wage (about $3/hr on average 1, that can’t even buy you a cup of coffee these days).

The purpose of the panel was two-fold:

- To bring awareness to the lack of guidelines for paying subjects fairly

- To begin outlining how to pay subjects fairly

While the panel was only the beginning of what will (hopefully) be a series of conversations, here are some of the main points discussed, followed by some recommendations and resources.

What Do We Consider Fair Pay?

There are no global standards which dictate fair wage, this results in participants in different regions getting paid differently. Even the discussion regarding what is fair is complicated – is fair pay a wage that supports some standard of living or is it a wage that meets some minimum wage standard? The problem is further exacerbated when we consider crowdsourced studies. The requester and the participants might be located all over the world. So how do we decide what a fair compensation is?

Setting a high bar for payment might disadvantage less well-funded universities from participating in research. One of the suggestions that came up in the panel discussion was paying the minimum wage for the requester’s location. This approach does not address the problem of inequity between locations. A minimum wage from one location might be less than the minimum wage in another.

And simply setting a blanket-high wage runs into potential problems in a crowdsourcing environment, where the market wage is low. Paying significantly above market rate may be seen as undue influence or coercion. However, this is less of a harm than underpaying the workers.

We need research to better understand workers, their expectations and the invisible labor that goes into crowd work. This will help us develop a more humane and compassionate pay scale. Meanwhile, as individual researchers we can take steps to better improve our compensation by thinking of crowdsourced workers as both workers and people.

Think About Crowdsourced Workers as Workers and People

While this statement sounds obvious, often the labor conditions of workers are not an explicit consideration of researchers; after all we are not managers, we are not responsible for their working conditions beyond our study, right? By taking a subtle shift in perspective, one focused on labor rights, the researcher becomes responsible for considering how their study impacts the working life of their participant.

One of the main themes that came up in the panel was a focus on transparency and fair working conditions. Paying attention to working conditions can include:

- Being explicit and transparent to workers about what you expect the study conditions to entail

- Being explicit and transparent to workers about what you are offering to pay them and why

- Factoring in bathroom breaks, life moments, etc. so that participants have ample time to complete a task without fear of losing compensation

Is it Our Responsibility to Think about This?

The title of the panel after all is “Wait…I never signed up to be an economist?” So why is the onus of fair pay placed on researchers? Why can’t we place the responsibility on research institutions responsible for reviewing experimental design, like the Institutional Review Board (IRB) or a publisher or professional organization sponsoring a conference, such as IEEE? At the moment, neither organizations enforce or have standards around fair pay. In some instances, the IRB will even flag that paying participants too much may cause undue incentives in the experimental setup. Further, as outlined in Steve Haroz’s blog post, the IEEE guidelines provide no mechanisms for raising ethical concerns.

Enforcing Fair Pay

Panelists touched on three different avenues through which fair pay can be enforced: platforms, social media, and research communities.

Platform-based enforcements rely on technology to mediate the difference in expectations and behavior between crowdworkers and researchers. For example, by using Wage Pledge, workers are given avenues through which they can report researchers that do not deliver the payment or working conditions that were promised. Similarly, Prolific mediates disputes between workers and researchers.

Another avenue of enforcement happens through social pressure. Subreddits and other messaging boards are used by workers to track and call out bad behavior when it comes to not paying people fairly.

Research community-based enforcement does not currently exist in visualization. We are hoping that this panel sets into motion more explicit action from our research community. This type of enforcement may look like:

- Setting paper submission guidelines that ask researchers to specify participant compensation.

- As a reviewer and paper chair, having the ability to reject or refuse to review research that chose to ignore ethical payment as part of their experimental considerations.

What’s Next?

There is still so much to consider beyond this panel. Namely, there are discussions that can (and should) be had by organizing committees to formalize a set of guidelines for ethical pay in studies.

While we wait, as researchers we can make the choice within our research to think about the ethical standards of our experiments:

- How much are we paying individuals? Is this wage a living wage?

- How will I pay participants that take longer to conduct the study?

- Have I articulated the working conditions I expect of the working conditions in my study? What avenues do workers have to communicate grievances or concerns?

For instance, there is great work being done by Rivera et al. that proposes a design space for considering crowd-sourced tasks as opportunities to help workers develop employable skill sets.

This leads to a natural next question: Do we understand our crowdsourced worker’s wants and needs? Other fields like HCI and CSCW have explicitly explored this question. Should we collaborate with researchers in these fields to learn more or do we need to conduct our own studies?

Ultimately, this panel exposed that there is still more work that needs to be done as part of our responsibility to conduct research in an ethical manner. We’ve included a list of resources and tools below.

Resources

Tools:

Papers:

- On the invisible labor of crowdworkers

- A review of crowdworker pay

- The career goals of crowdworkers

- Challenges to collective action for crowdsourced workers

Panelist Statements

Acknowledgements

Thank you Danielle Szafir, Steve Haroz, and Alex Lex for your edits!

Footnotes: